Author: Salayla Elmasry

Water doesn’t respect borders- but in South Asia, it’s being turned into a weapon. As Pakistan’s

rivers run thinner under the strain of climate change and upstream control, a new form of

pressure is emerging from New Delhi: dam diplomacy. In 2025, the Indus Waters Treaty, long

held up as a rare success story in India-Pakistan relations, is no longer just about engineering

or irrigation. It’s about survival, sovereignty, and the growing fear in Islamabad that its lifeline

is slipping away, one concrete barrier at a time. The next war between India and Pakistan may

not be fought over land or ideology- but over the slow, silent theft of a river, as upstream dams

tighten their grip on the Indus and water becomes the most powerful weapon never officially

declared.

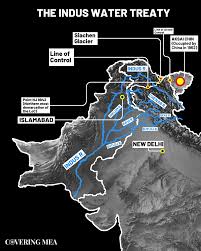

Pakistan’s lifeline flows through its rivers, and the three western Indus tributaries – the Indus,

Jhelum and Chenab – carry roughly 80% of the basin’s waters. These rivers irrigate about 90%

of Pakistan’s crops and power its hydropower dams. Yet in 2025 that lifeline has become a

battleground. In April, after a militant attack in Kashmir, India announced it was putting the

1960 Indus Waters Treaty “in abeyance” – effectively threatening to throttle the flow to

Pakistan unless Islamabad cuts off cross-border terrorism. Pakistan’s farmers reacted with

alarm, calling such moves “an act of war”. Already facing a water deficit (rainfall and snow

last year were 20–25% below normal, Pakistan now watches upstream dams and canals that

could dramatically reduce its share of the Indus system.

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT), brokered by the World Bank in 1960, was supposed to prevent

exactly this: it allocates the three eastern rivers (Ravi, Beas, Sutlej) to India and reserves the

western rivers for Pakistan. In other words, India controls all headwaters but Pakistan owns

virtually all their flows. The treaty codifies that India may use the western rivers for only

limited “run-of-river” hydropower and irrigation, “circumscribed” by strict engineering limits.

Crucially, the IWT contains no clause allowing either side to suspend or withdraw unilaterally;

it was written to endure wars and tensions. Pakistan’s government thus insists the treaty remains

binding, warning that “any attempt to stop or divert the flow of water belonging to Pakistan”

is an “act of war”. As one Pakistani expert put it, the IWT is the backbone of the country’s

agriculture. Any significant cut in flows would imperil irrigation of wheat, rice and sugarcane,

risking food shortages and spikes in farm costs.

Yet India’s recent actions have flown in the face of both the letter and spirit of the IWT. In the

past two years New Delhi has pushed ahead with key projects on the western rivers – notably

the Kishanganga and Ratle hydroelectric plants in Indian-administered Kashmir – that Pakistan

says will reduce its downstream flows. Pakistani officials point out that these dams, though

labeled run-of-river, involve storage and design features (pondage levels, spillways, outlets)

that go beyond what the treaty explicitly permits. Islamabad has repeatedly invoked the treaty’s

dispute-resolution process, first seeking a World Bank neutral expert and then asking a sevenmember Court of Arbitration (CoA) to review India’s designs. India countered by accusing

Pakistan of “dragg[ing] out” the process and arguing that Kishanganga and Ratle are allowed

under Annexure D of the IWT. Behind the scenes, Delhi has even demanded a wholesale treaty

revision under Article XII(3) – a bid to unilaterally rewrite the rules – which Pakistan charges

is itself a treaty breach.

In practice, this has generated parallel legal tugs-of-war. Pakistan formally requested arbitration

in 2016; India instead asked for a neutral expert on 4 October 2016 (Article IX, Annexure F).

The World Bank blocked appointments for several years, hoping for a bilateral deal. Eventually

a PCA Court of Arbitration was constituted in early 2023, even though India boycotted it,

denouncing the tribunal as “illegally constructed” and insisting only a neutral expert should

decide. In July 2023 the PCA CoA overruled India’s objections and declared itself competent

to hear Pakistan’s case. And just last month – in a June 2025 Supplemental Award on

Competence – the tribunal emphatically reaffirmed that India’s attempt to hold the treaty in

“abeyance” cannot stop the arbitration. The tribunal pointed out that the IWT requires disputes

to be settled by the CoA or neutral expert, not by political fiat, and that the treaty “does not

provide for unilateral abeyance or suspension”.

India has flatly rejected these rulings, with its foreign ministry calling the tribunal itself a

violation of the IWT. Instead, Indian officials have couched their moves as sovereign responses

to terrorism, hinting at invoking doctrines of necessity or countermeasures under international

law. But legal scholars note the IWT’s explicit rigidity: it was “prescriptive and rigid” with no

suspension clause and was “designed to operate independently of political or military tensions”.

In fact, under general watercourse law – reflected in the UN Watercourses Convention and

customary practice – an upstream state like India has a duty of equitable use, no significant

harm, and cooperation. If India were seriously to cut or hold back water, Pakistan could

credibly argue a breach of those principles. Already, an 80% drop in flow was registered at key

Pakistani waterworks in early May when India did “maintenance” on a Kashmir barrage– a

stark preview of what withholding flows could mean.

Climate change only deepens Pakistan’s stakes. National experts warn that warming is

collapsing the Indus watershed: snow cover fell 23.3% between late 2023 and spring 2024, and

glacier melt rates have jumped. The Indus basin (with over 7,200 glaciers) is among the world’s

most vulnerable, and by century’s end could lose 30–75% of its ice, radically altering seasonal

flows. Pakistan’s own storage capacity is pitiful – its reservoirs hold barely 10% of annual river

flow– so it cannot buffer extended shortages. In 2025 the water is already “20-25% lower than

last year”. India’s dam-building and data-holding policies exploit this fragility: after halting

treaty cooperation, Delhi can stop sharing flood and flow data, jeopardizing Pakistan’s

emergency planning.

Seen in this light, many analysts view India’s new water assertiveness as overt geopolitical

leverage. Water diplomat Happymon Jacob observes that India is narrowing its entire bilateral

agenda to pressure over Kashmir via the IWT. Prime Minister Modi’s rallying cry – “not even

a drop of water goes out” – and the planned doubling of an old Chenab canal (from ~40 to 150

m³/s), signal a campaign to tie Pakistan’s hands. As CSIS water expert David Michel notes,

constructing the massive dams and canals needed to fundamentally choke Pakistan’s supply

would take years– but Pakistan is already living with the uncertainty, given how crucial even

routine releases are.

To safeguard its lifeline, Pakistan must act not just defensively, but strategically. Legal recourse

is essential—but so is narrative power. Islamabad must frame India’s unilateralism not as a

bilateral technical dispute, but as a precedent-setting breach of international water law with farreaching global implications. The stakes are no longer confined to the Indus Basin; in an era of

accelerating climate stress, allowing an upstream state to weaponize a transboundary river

undermines the entire architecture of international environmental law. Pakistan should continue

to press its case through the Permanent Court of Arbitration, but also leverage multilateral

forums—from the United Nations to COP negotiations—to highlight how India’s actions

violate core principles of equitable and reasonable use, no significant harm, and prior

notification, as embedded in the UN Watercourses Convention and customary law.

Crucially, India’s suspension of treaty obligations and attempt to reinterpret or override

provisions also conflict with the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1969)—the

foundational legal instrument governing how states enter, interpret, and comply with treaties.

Under Articles 26 and 27 of the Convention, every treaty in force is binding and must be

performed in good faith, and a state may not invoke internal pressures or domestic law to justify

non-compliance. Article 60 explicitly prohibits the suspension of treaties unless a “material

breach” has occurred—a threshold not met by any current action of Pakistan. By unilaterally

placing the Indus Waters Treaty “in abeyance,” India risks setting a dangerous precedent that

weakens treaty integrity globally.

Because at its core, the Indus Waters Treaty is not just a water-sharing agreement—it’s a

security pact in disguise. It was designed to keep peace flowing even when diplomacy failed.

If India is permitted to unilaterally rewrite, suspend, or sidestep it, the consequences will ripple

far beyond South Asia. The message to other upstream powers—from the Nile to the Mekong—

would be clear: water is no longer a shared resource but a sovereign instrument of power. For

Pakistan, this isn’t just about dams, turbines, or flow data. It’s about defending the very idea

that international law constrains might, and that even a vulnerable downstream country has the

right to exist within a rules-based order. If the world fails to defend one of the most durable

water treaties ever written, it may soon find itself navigating a future where rivers no longer

bind nations together—but break them apart.